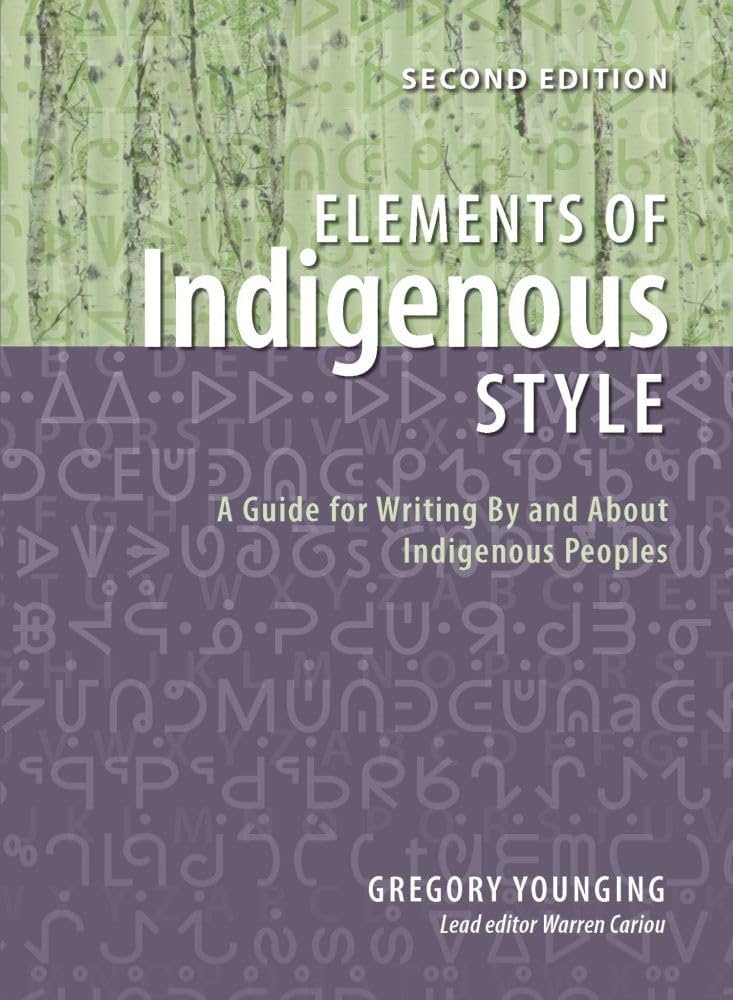

The second edition of Gregory Younging’s Elements of Indigenous Style was released last month. A launch event with editors Warren Cariou and Lorena Sekwan Fontaine will be held on Wednesday, February 12.

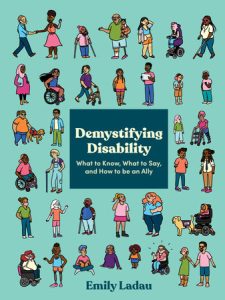

A welcome new resource: Demystifying Disability

Every once in a while, a new resource, or a new edition of an old resource, comes along that gets those of us who work with words very excited (think Chicago Manual of Style, Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, Canadian Press Stylebook). The arrival of Greg Younging’s Elements of Indigenous Style: A Guide for Writing By and About Indigenous Peoples in 2018 was one such moment for me; now thick with stickies and bent from use (and spilt tea), my copy has never left my desk.

Every once in a while, a new resource, or a new edition of an old resource, comes along that gets those of us who work with words very excited (think Chicago Manual of Style, Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, Canadian Press Stylebook). The arrival of Greg Younging’s Elements of Indigenous Style: A Guide for Writing By and About Indigenous Peoples in 2018 was one such moment for me; now thick with stickies and bent from use (and spilt tea), my copy has never left my desk.

Demystifying Disability: What to Know, What to Say, and How to Be an Ally, by Emily Ladau, has also taken up permanent residence on my desk since it arrived in 2021. This is a must-read for everyone, but the chapter on language (“So, What Is Disability, Anyway?”) is indispensable for writers and editors. Ladau, who describes herself as having multiple disabilities and therefore speaks from a lifetime of experience, pulls no punches. The text is clear and direct, with headings like “Just Say It: ‘Disability,’” “Drop These Words,” and “Find a Better Insult.” There’s a list of euphemisms to be ditched, like “differently abled,” “mentally or physically challenged,” and, yes, “special needs.” The terms included in a four-page table telling us to “say this” and “not this” are also discussed and unpacked throughout the book.

But in case this makes you think the language around disabilities is simple and straightforward, stop right there; it’s anything but. Perhaps the most important message of the book is that “disability is not one-size-fits-all.” Ladau says there is no singular disability experience: “We’re each our own person, and everyone’s thoughts and experiences are different. Because disability exists in infinite forms, even people who share the same diagnosis (if they have one) don’t have identical experiences.” By extension, “the way people who have a disability talk about their disability is their choice.”

Case in point: Ladau uses both “person with a disability” and “disabled person” in the book, because they reflect two of the main ways of referring to disability. Person-first language (PFL) puts the word “person” before any reference to disability, meaning disability is something a person has rather than who they are; it respects their personhood. Identity-first language (IFL) acknowledges disability as “part of what makes a person who they are” and “an identity that connects people to a community, a culture, and a history.” Whether a person uses PFL or IFL is their choice.

Moving beyond the specific language issues, Ladau also addresses intersectionality in relation to disability—“disability can intersect with any and all other identities”—and the need to be constantly aware of our privileges and biases. Her discussion on ableism—“attitudes, actions, and circumstances that devalue people because they are disabled or perceived as having a disability”—reveals the shocking extent to which those attitudes are ingrained in society and to which disabled people are affected by them, day in and day out, whether in language or lack of accessibility or interpersonal interactions.

It is the job of editors in particular to be sensitive to all forms of bias and discrimination in language, no matter how subtle or hidden. This requires that we educate ourselves, so we know what to look for, both in ourselves and in the texts we edit, by reading, and rereading, books like Demystifying Disability.

In the conclusion to her book, Ladau addresses the fact that we will all make mistakes; none of this is going to be “smooth, simple, or straightforward.” When we do get it wrong, we should start by apologizing, not out of guilt but with “a true openness and willingness to learn”—recognizing that being truly accountable is more about the actions we take next to bring about change in ourselves and, ultimately, in the world in which we live.