When it comes time for an author to review my edits, having a meeting with them by phone or in person can lead to changes that might not happen when the conversation happens only on the edited page.

Editing consciously

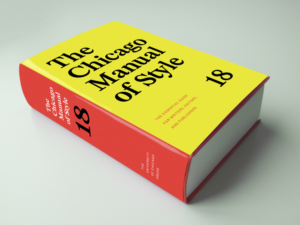

The hearts of editors beat faster in April when the University of Chicago Press announced that a new edition of the Chicago Manual of Style, number 18, would be released in September.

The hearts of editors beat faster in April when the University of Chicago Press announced that a new edition of the Chicago Manual of Style, number 18, would be released in September.

It’s come a long way since the 1st edition of 1906, and even since the first edition I owned, 1982’s 13th edition. The University of Chicago Press has been mixing things up in recent decades, changing the cover design and colour. The 18th edition has a yellow cover and is 1,192 pages long—40 pages longer than the 17th edition (published in 2017) and nearly 1,000 pages longer than the 1st.

As editors wait to crack open the distinctive red-orange spine, we are speculating about what changes may be coming for citations, capitalization, hyphenation, and, of course, commas. According to the University of Chicago website, major changes in the new edition include “updated and expanded coverage of pronoun use and inclusive language, new coverage of Indigenous languages,” and an expansion of CMOS’s “traditional focus on nonfiction . . . to include fiction and other creative genres.”

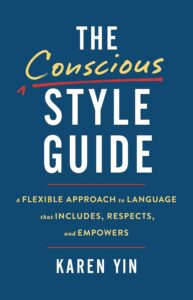

In the meantime, there’s a brand-new style guide that is also well worth a look: The Conscious Style Guide by Karen Yin. Yin, a copywriter and editor, is the founder of ConsciousStyleGuide.com and The Conscious Language Newsletter, as well as Editors of Color and AP vs. Chicago.

In the meantime, there’s a brand-new style guide that is also well worth a look: The Conscious Style Guide by Karen Yin. Yin, a copywriter and editor, is the founder of ConsciousStyleGuide.com and The Conscious Language Newsletter, as well as Editors of Color and AP vs. Chicago.

Yin explains the motivation behind the Conscious Style Guide website as her desire “to gather style guidance on compassionate, mindful, empowering, respectful, and inclusive language in one place.” In her book, Yin delves into the philosophy behind what she has termed “conscious language.” It’s a thoughtful and thought-provoking read, with numerous examples and key points throughout. Three things that stood out for me on my first read:

Conscious language is about promoting equity. Yin emphasizes the importance of words and their ability to change the world. She writes, “The truism ‘Words have power’ may strike you as lackluster if you’ve heard it before, but the phrase itself is powerful. It reminds us that we, the users of words, have power.” We have the power to change the way we see other people as well as the social structures that oppress and exclude people who appear to be different. Yin says, “By using language that includes, confers respect, and self-empowers, we have the power to shift entrenched attitudes, especially our own.”

Conscious language is a philosophy, a mindset. Ultimately, it is about precision, choosing the correct word for the context and the purpose—a goal that will sound familiar to editors and to the writers we work with. Yin does not set out rules that must be followed or lists of words that can or can’t be used. She encourages us to think about what we want to say, who we want to say it to, and how our words might injure listeners (not hurt their feelings but actually limit their potential and freedom) or heal and free them. She includes a section on best practices we can consider and try and a list of doubts readers might have about conscious language. These sections help us discover what works for us. I found they also illuminated some of the questions I’ve been grappling with in both my editing life and my daily life.

Which leads neatly into my third take-away:

Conscious language is a practice—like art or yoga or editing. Yin makes this point in the introduction, adding that her favourite definition of “practice” is “translating an idea into action.” It’s an ongoing process and constantly changing. I know that as I work to translate the idea of conscious language into my editing and my life, I will regularly dip into The Conscious Style Guide for advice.

As you wait for The Conscious Style Guide and CMOS 18 to arrive in your mailbox or at your local bookstore, you might want to check out some earlier WCEA blog posts in this conversation, focusing on conscious language, the language of disability, and Elements of Indigenous Style.

As I wrote this post, I heard rumours that work was underway on a revision of Elements of Indigenous Style. Last week the publisher, Brush Education, confirmed there would be a second edition published in 2025.