Thinking of attending an editing conference this year? Here’s our snapshot of the conferences in 2024.

Mastery in action

Every once in a while, a writing or editing project provides an opportunity to work with a person who is a master in his or her field. Most often, it’s someone who works with words—another writer or editor—but not always.

Last year, I had the good fortune to collaborate with Ted Grant. Known as “the father of Canadian photojournalism,” Ted has worked with a camera in his hands for more than 60 years. The National Archives of Canada has almost 300,000 of his photos—the largest collection by a single photographer in Canadian history—in addition to the National Gallery of Canada’s 100,000 images.

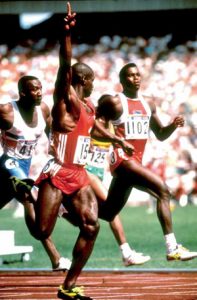

Ted has photographed people all over the world—in wars, politics, and sporting events, or just doing what they do. His iconic shots include Pierre Elliott Trudeau sliding down the banister at the 1968 Liberal Party leadership convention and Ben Johnson crossing the finish line in the 100-metre race at the 1988 Olympics, index finger raised in victory as he looks back at arch-rival Carl Lewis.

An important category in Ted’s vast portfolio is medicine, and that’s how our paths crossed. West Coast Editorial Associates was hired to produce a small book for the 10th anniversary of the Island Medical Program (IMP), part of the University of British Columbia Faculty of Medicine. I had included the services of a photographer in the budget and also asked what was available in the way of archival photos. It turned out that Ted had approached the IMP not long after it began about taking photos of medical students as they learned and of faculty as they taught. He’d returned several times over the years, and the photos had appeared in a major exhibition at the University of Victoria. When asked if we could use some of the photos for the book, Ted graciously agreed. Even better, he was willing to take some new portraits to accompany several profiles of students, faculty, staff, and alumni.

The portrait sessions would be among Ted’s first since having his shoulder replaced, so my job included getting him to and from the locations and lending him an arm on slippery sidewalks. That meant extra time together, which he filled with stories from his extraordinary career. Best of all, though, was watching him at work.

For each portrait, Ted made sure the person was busy, not simply looking at the camera. He always aimed to be “invisible,” at the periphery, so as not to distract his subjects. Sometimes he took only a handful of shots before he had what he wanted. Other times it took longer to get it right. But in the end, he always got it right: beautiful, intimate images of people being themselves.

When describing how he got a particularly important shot in the past, Ted often finished by saying it was pure luck. Like catching Trudeau sliding down the banister—pure luck! But no: the truth is that he’d put himself in the right place at the right time (you might call that instinct, or brilliant planning) and with only one chance, and a fraction of a second in which to act, he knew exactly what to do. That’s called pure mastery. And what luck for me to have seen it in action.

This Post Has 3 Comments

Comments are closed.

Hi Merrie-Ellen,

Thank you for such a wonderful description of how

fortunate I am in having the life I’ve enjoyed.

Part of the magic has been people of your caring

calibre as working mates. I’d say many of my

best assignments have been with a writer as

helpful as yourself. “It’s the TEAM EFFORT”

that brings the luck! Luck doesn’t happen because

of one person! Good teams are hard to come by, but

ours? “WAS THE BEST!” cheers, Dr. ted. 🙂

Thank you so much for your kind words, Dr. Ted. I’m looking forward to the next team effort!

This is a great story about an unusual collaboration. Thanks for telling it!