Everything in its place

As an indexer, I tend to be obsessive about organizing things alphabetically—the books on my shelves, the spices in my cupboards, the DVDs and CDs in the basement . . . Of course Joan Aiken should come before Kate Atkinson, who should come before Jane Austen. And caraway should come before cardamon and cayenne.

As an indexer, I tend to be obsessive about organizing things alphabetically—the books on my shelves, the spices in my cupboards, the DVDs and CDs in the basement . . . Of course Joan Aiken should come before Kate Atkinson, who should come before Jane Austen. And caraway should come before cardamon and cayenne.

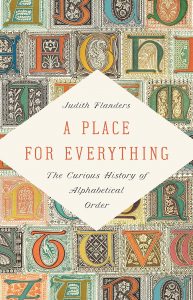

When I stumbled upon A Place for Everything: The Curious History of Alphabetical Order, a new book by Judith Flanders, the title made me wonder, why does a come before b and t before w? Why doesn’t the alphabet start z y x w and end with f i n?

However, this is not what Flanders is interested in. In the Preface she dispatched my question quickly and succinctly: “The alphabet, as far as we can tell, was written from its very earliest days in a set order. Why, we don’t know, although ease of memorization seems possible, even likely.” (To find out more about the alphabet itself, I’ll have to plan a trip to the Museum of the Alphabet in North Carolina when travel restrictions are lifted. Or maybe check out David Sacks’ Letter Perfect: The Marvelous History of Our Alphabet from A to Z.)

Since the book isn’t about the sequence of the letters, you might wonder how there can be over 200 pages just on alphabetical order. As it turns out, it took several hundred years for alpha order as we know it now to become the standard for sorting things in our alphabetic system (as opposed to systems based on ideograms or syllabaries, which are briefly touched on in the book). As Flanders notes, “Scientists today suggest that experts in any one field can routinely remember up to a few hundred items devoted to their own specialty. Once the numbers rise above that . . . memory prompts become necessary.”

Numerous sorting methods have been, and still are, used in addition to alphabetical—for example, chronological, geographical, hierarchical. Items within each of the resulting categories are then arranged alphabetically. For centuries, scribes arranged words by their first or first two letters. In first-letter alphabetization, Aiken, Austen, and Atkinson would be grouped together, but they could be in any order. In second-letter, Flanders says, you could have “Cato, Calpurnia, Catullus” as a correctly ordered list because you are just considering the first two letters of the word.

Flanders describes how “absolute alphabetical order,” where all letters of a word are considered, came to be the norm and also traces the development of tools for organizing material. People always laugh when they realize “index cards” are called that because they were used for writing indexes, but I was surprised to learn that the first index cards were decks of playing cards, which in the 18th century “were printed with the suits and values on one side, . . . but the reverse was left blank.” Abbé François Rozier was commissioned to produce an index of publications by the Académie des Sciences in Paris, and he decided that playing cards were the best medium for creating this list.

A Place for Everything is a trove of similar fascinating details about books and publishing, as the history of alphabetical order includes stops at herbals, biblical concordances, legal tomes, library card catalogues, and elements of printed books besides the index—the table of contents, chapter and paragraph breaks, and marginalia, which became footnotes.

Shortly after I got the book, I was excited to see that Judith Flanders was to give the Peter and Ana Lowens Lecture, an annual lecture presented by UVic Libraries Special Collections relating to the Victorian period. I assumed it would be on alphabetical order, so signed up without looking too closely at the fine print. As it turned out, this year’s lecture was held in collaboration with the Crafting Communities project, a year-long series of roundtables and workshops co-organized by the University of Victoria, the University of Manitoba, and the University of Alberta. Flanders was speaking on “A Handful of Victorian Objects.”

Screen capture from Zoom presentation

The talk—on Zoom, of course—was well worth attending even though it wasn’t on the alphabet. Flanders described how by the 18th and 19th centuries, people in England were beginning to have what she called, with “great academic rigour,” more “stuff” in their houses. She talked about the introduction of curtains and the closed cooking range, and then she moved on to the desk, which, in a way, brought us back to indexing and organizing. As Flanders said, “The Victorian era, even in the household, was a place and time of classification . . . an age of selections and collections of abstracts and compilations, anthologies, genealogies, indexes, catalogs, bibliographies, and local histories.” With its big and little pigeonholes, drawers, racks for plans and charts, and little lettered boxes, the desk was a solid exemplar of the idea of a place for everything and everything in its place.

* * *

I went down several rabbit holes as I was writing this blog. For one, on May 28, Crafting Communities launched its new website, podcast, and virtual exhibition. Check out the website for tips on creating hair art.

As I read about the alphabet, I found myself humming a song I’d heard decades ago on Sesame Street.

And when I was checking out something Judith Flanders said about the closed cooking range, I found a hilarious blog by Sarah Lohman, who studies and recreates historical American food. She spent one day as a 19th-century domestic in her New York City apartment, serving her fiancé and a visiting friend. Best line: “So far the cat has been the most demanding member of the household.”