There are many editing and plain language conferences planned this year.

A visit to one of the world’s largest rare book libraries

One afternoon last April, on a quest to gather information about biologist and author Rachel Carson for a book I would be writing, I guided my behemoth rental car along the grey streets of New Haven, Connecticut. The windshield wipers swick-swacked as I peered through rods of rain, seeking a parking spot. I glimpsed my destination—Yale University—but soon overshot its impressive stone and brick buildings. I turned up and down streets and eventually settled for a dingy parkade several blocks away.

The downpour had relaxed into a drizzle as I set off on foot in search of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. At the corner of Rose Walk and Wall Street, I met a hefty, whitish, pocked cube of a building stranded on the edge of a bleak sunken plaza. Compared with the grand Stirling Memorial Library across the street, the Beinecke was, in all honesty, an eyesore.

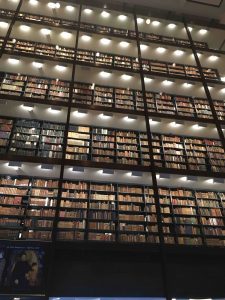

I descended the half dozen steps to the plaza and scurried to the building to walk beneath its overhang. When I reached the revolving glass entrance door, I stamped my boots, shook off my rain coat, and passed into an enchanted hall. Warmth and soft light enveloped me. Ahead rose a tower of floor-to-ceiling glass, behind which sat books. Shelf upon shelf of books. Biblioecstasy.

The Beinecke opened in 1963 to house Yale’s collection of rare books and manuscripts, including a Gutenberg Bible dating to 1455 and John James Audubon’s Birds of America, printed between 1827 and 1838. In its 55 years, the library has acquired thousands of volumes and miles of other materials. The glass tower—the building’s interior core—holds 180,000 books, and underground vaults have room for a million more. To preserve the collections within these spaces, the temperature and humidity stay constant, and all but librarians are excluded. The building’s exterior design also plays a role: thin panes of white marble surrounded by grey granite (which together gave the pocked appearance I observed outside) let in filtered light but not the sun’s damaging rays.

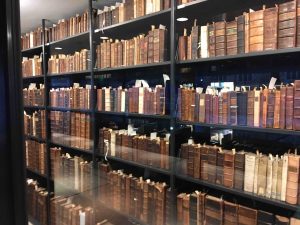

When I had collected my wits, I approached the reception desk to sign in. A security guard escorted me around the side of the glass tower, giving me an up-close view of leather-bound books on the forbidden side of the glass. He hustled me to a row of lockers, where I was instructed to leave my belongings, save the items I needed for my research. I kept a pad of paper, glasses, phone, and passport (not leaving that in a locker, no matter how secure!). The guard then ushered me down a flight of stairs, through a heavy glass door, and to his colleague, who examined my four items.

The Beinecke’s tight security is warranted. In 2006, a librarian noticed the blade of a hobby knife on the reading room’s floor. She consulted the sign-in documents for that day’s visitors and came across the name Edward Forbes Smiley III, a dealer in rare maps. The alert librarian called security, who confronted Smiley and discovered several stolen maps in his possession. He later admitted to stealing 97 maps, valued at about US$3 million, from libraries on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean, landing him with a hefty fine and jail time. Journalist Michael Blanding wrote Smiley’s story in a gripping account, The Map Thief (Gotham Books, 2014).

Satisfied that I didn’t have any tools of thievery, the security guard pointed me through yet another glass door into the reading room. I took an empty spot at a long table. A woman on the other side pored over an ancient book propped on foam. She turned the pages with exquisite care using her white-gloved left hand, while her right hand tapped the keys of a MacBook. What juxtaposition. I felt a pang of jealousy that I wasn’t about to examine a centuries-old book with fragile, brown-edged pages.

The feeling subsided when I went to the circulation desk to obtain an HB pencil and the first of 10 previously requested boxes. I spent the next four hours leafing through folder after folder containing draft manuscript pages, field notebooks, letters, photographs, newspaper clippings, and comic strips, all of them by, to, or about Rachel Carson and her lifework. From the 1920s to the early 1960s, Carson brought the wonder and workings of oceans and marine life to a public readership before penning the work she is most remembered for: Silent Spring, an alarm bell about the hazards of flagrant pesticide use.

Given her concerns about the effects of synthetic pesticides on wildlife and people, Carson would likely have been pleased to know that the Beinecke, where she bequeathed her papers, employs a non-toxic method of pest control in its stacks. In the 1970s, a shipment of books from Europe introduced a beetle that dines on paper and bookbindings. Instead of fumigating with pesticides, the library accepted a Yale entomologist’s recommendation of deep-freeze treatment, whereby materials are sealed in plastic bags and held at −30°C for three days. Time in the “Blast Freezer,” as staff call it, has become automatic treatment for all library acquisitions, and the method is also now used by other libraries.

When I had gone through all 10 boxes, snapped umpteen photos, and scribbled pages of notes, I reluctantly returned to the security guard’s desk. He re-examined my belongings and this time had me pat my pockets to prove nothing lurked within. I retraced my steps to the lockers, around the glass tower to the front reception, through the revolving door, and out to the empty plaza. As I walked beneath grey clouds, thankfully no longer releasing their contents, I could still feel the hush of Beinecke’s reading room. I glanced back at the marble and granite building. Its transformation startled me. The sculpted cube looked rather grand, almost floating on the air.

I highly recommend a dose of biblioecstasy.