An eye-opening experience

On a sunny, breezy evening in Montreal, my two daughters, my nephew, and I walked through the front door of an unassuming-looking restaurant named Onoir. The host welcomed us and gave brief instructions: place our bags, coats, silenced phones, and any other loose items into a locker, lock the locker, and keep the key. We were then shown to a lounge and seated at a small table with four menus. We eyeballed the options and were ready when a server came to take our orders: we each chose a three-course meal, with all of us also brave enough to select one or two “surprises” among the courses and beverages. Next, the server directed us to go up a set of stairs and give our table number to “D,”[1] who would be waiting for us. “OK, kids, let’s see how this goes,” I said as we got up. My nephew smirked and my daughters both rolled their eyes.

Up the stairs, we found a dimly lit anteroom and were greeted by D, who shook my hand but made no eye contact. He then turned to my nephew and asked him to place his hands on D’s shoulders from behind and for the rest of us to do the same to form a human train. “Êtes-vous prêtes? Are you ready?” D asked in both languages, and we were off. He opened a door and led us along a short corridor, around a bend, and past a heavy curtain into a dark room. Without even a sliver of light, our eyes had nothing to adjust to. We couldn’t see a thing for the next few hours as we enjoyed—by taste, touch, aroma, and sound—an exquisite meal.

Our experience at Onoir that evening brought several things into focus for me.

The first was how inept we all were without our sight—“Oops, I got a forkful of nothing again!”—but also how my hearing took over as my dominant sense. Sure, I was using my fingers to feel my way around the place setting: smooth metal of knife and fork; little bumps edging a plate; cool, moist condensation on water glass; soft, greasiness of butter pat—“Ugh, stuck my finger right in it. Watch what you’re doing,” I muttered. But it was my hearing that dominated: the clunk of a glass set down too hard; the clatter of a knife on the uncarpeted floor; the scrape of my nephew’s chair as he attempted to retrieve the knife—“I’ll get it back in a twinkle of an eye,” he said; the subsequent chortle from my elder daughter—“Shh, not so loud, honey,” I whispered; the slurp as my younger daughter sucked in a spoonful of soup—“Manners, kids, please,” I hissed, my eyes bugging out; the chatter of guests at other tables—an older couple one way, a group of three adults and two young children the other way; the lilt and occasional crescendo of background orchestral music. So much rich sound!

The second revelation—as you’ve likely noticed in reading this far—was the number of phrases and idioms related to eyes and sight in everyday speech. It had never occurred to me before. When we first took our seats, with D’s gentle guidance, I said something like “Well, kids, here we are! I’ve been looking forward to this.” One of my daughters guffawed. “Looking forward?” To which I replied, “Yes, ironic wording. I can see that.” And on the conversation went until we’d exhausted the turns of phrase we could come up with. It took a while: there are a lot. It was, to be glaringly obvious, an eye-opening experience to realize how sight-centric our language can be. We switched to thinking up phrases about hearing and sound and made a good list, but with fewer items. Then smell: harder still, and most were nose-related, not smell-related. We stopped there.

My third insight of the evening was that D guiding us through our meal was similar to how writers of “alternative text,” or alt text, guide readers with visual disabilities through the content of an image. Alt text describes images in words so that someone listening to a story, article, or other text being read by a screen reader can also hear a description of any accompanying images. The use of alt text goes further: if an image won’t load or its resolution is too low to display details, then alt text can inform any user of the image’s content. Alt text also helps search engines zero in on relevant information for web users. Alt text is just one tool of many that writers, editors, and designers can use to improve a document’s accessibility, as partner Amy Haagsma wrote about last year.

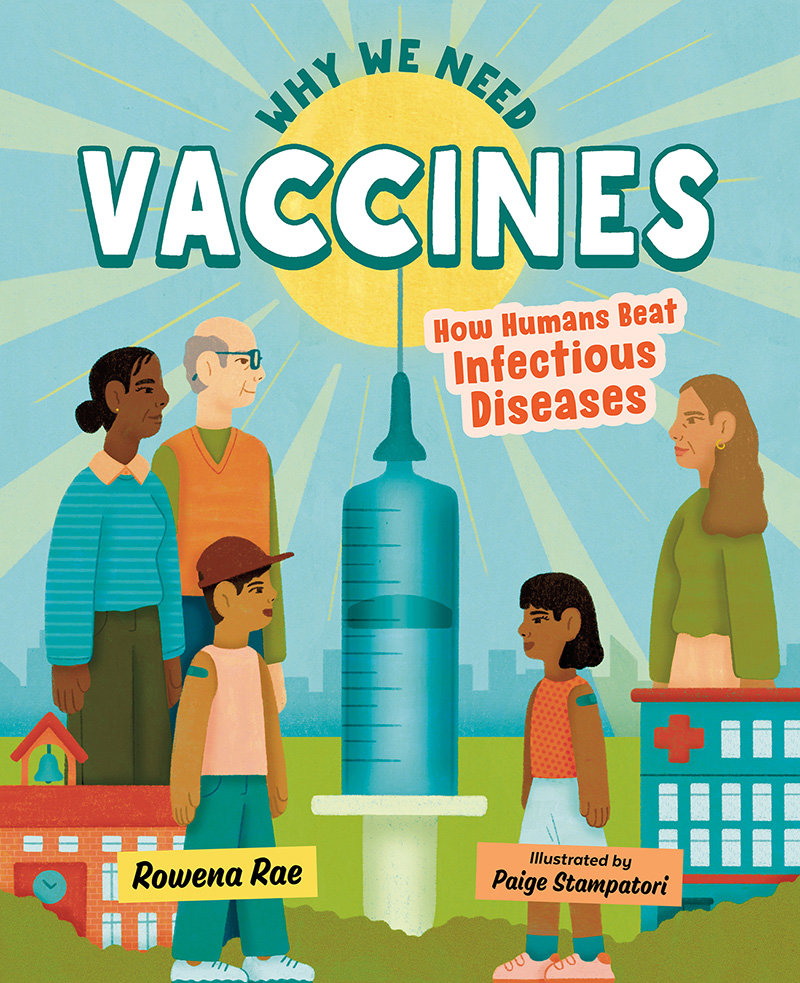

It takes practice to describe an image accurately and to state only what the image shows, not to interpret the content. For example, there’s a difference between the alt text for the photo at the beginning of this blog post and its caption. The alt text is “Three smiling teens with their arms around each other’s shoulders standing outside a brick building with a sign reading ‘Onoir’ above the door,” while the caption—“Leaving Onoir after an excellent meal and a humbling experience”—gives only my interpretation. And though a picture is supposedly worth a thousand words, alt text must be far shorter to paint a picture in a useful way.

For the past year, two of my WCEA partners and I have been working on a project to write alt text of 140 characters or less (spaces included) for images—photos, drawings, maps, graphs—in documents destined for public online access. Fortunately, when there’s more to say than we can possibly fit into 140 characters, we are permitted to add a “long description” that accompanies the alt text. In the course of this work—which I’ve grown to enjoy immensely for the challenge of really viewing an image at face value and trying to strip away my biases and my desire to analyze and interpret—we’ve come across some excellent resources. If you find yourself writing alt text or wanting to learn more about accessible publishing, then you may find these helpful in addition to Amy’s earlier post:

- Accessible Publishing Learning Network has articles such as “Best practices for writing image descriptions” with detailed examples and links to further resources.

- Carleton University’s Web Workshops offers a free, self-paced, online course titled “Accessibility Training.” Module 3 discusses alt text for images.

- Complex Images for All Learners: A Guide to Make Visual Content Accessible by Supada Amornchat is a booklet about writing alt text for complex images such as graphs, charts, maps, and other data-heavy visuals.

- The DIAGRAM Center’s Poet Image Description microsite offers resources for and practice at describing images.

- WebAIM has an online tutorial titled “Alternative Text.”

You may also be interested in online training from one of these organizations:

- Accessibility Services Canada offers live webinars on many aspects of document accessibility, including alt text. There is also a bank of previously recorded on-demand courses.

- BookNet Canada hosted a Tech Forum about alt text last year and has another webinar coming up on June 25, 2024.

- CreativePro runs an annual virtual event, the Design + Accessibility Summit. This year’s event is October 8–11, 2024. Geared to design professionals, it covers much more than alt text. The agenda with presentation titles, synopses, and speakers is already available.

- The DAISY Consortium has a long list of free webinars on accessible publishing and reading.

Back at Onoir, the four of us guessed the time at the end of our meal, before D led our human train back through the curtained doorway, around the bend, along the short corridor, and into the dimly lit anteroom. I was grateful for the soft lighting as my eyes flooded and adjusted. After we retrieved our belongings and paid the bill, we stumbled out the front door to a street with piercingly bright lights. My nephew turned on his phone, gasped, and held the screen toward me. We had been in Onoir for more than three hours. The time had gone by in the blink of an eye.

[1] Anonymized for privacy

This Post Has 0 Comments