Last name first?

I recently saw the movie Incandescence, a National Film Board of Canada documentary about the Okanagan wildfires of 2021 and 2023. As the credits ran, I realized the extensive list of acknowledgements was alphabetized by first name, rather than being inverted (placing the last name first, with a comma before the first name). I was watching Incandescence with WCEA partner Rowena Rae, and she also noticed this, asking if it was a common format for alphabetizing lists like indexes.

Coincidentally, a few weeks earlier, an indexer colleague had sent me a link to the index for the book German Philosophy and the First World War by Nicolas de Warren, from Cambridge University Press. Here, too, the names were not inverted and were alphabetized by the first letter of the first name (for example, “Aby Warburg” rather than “Warburg, Aby”).[1]

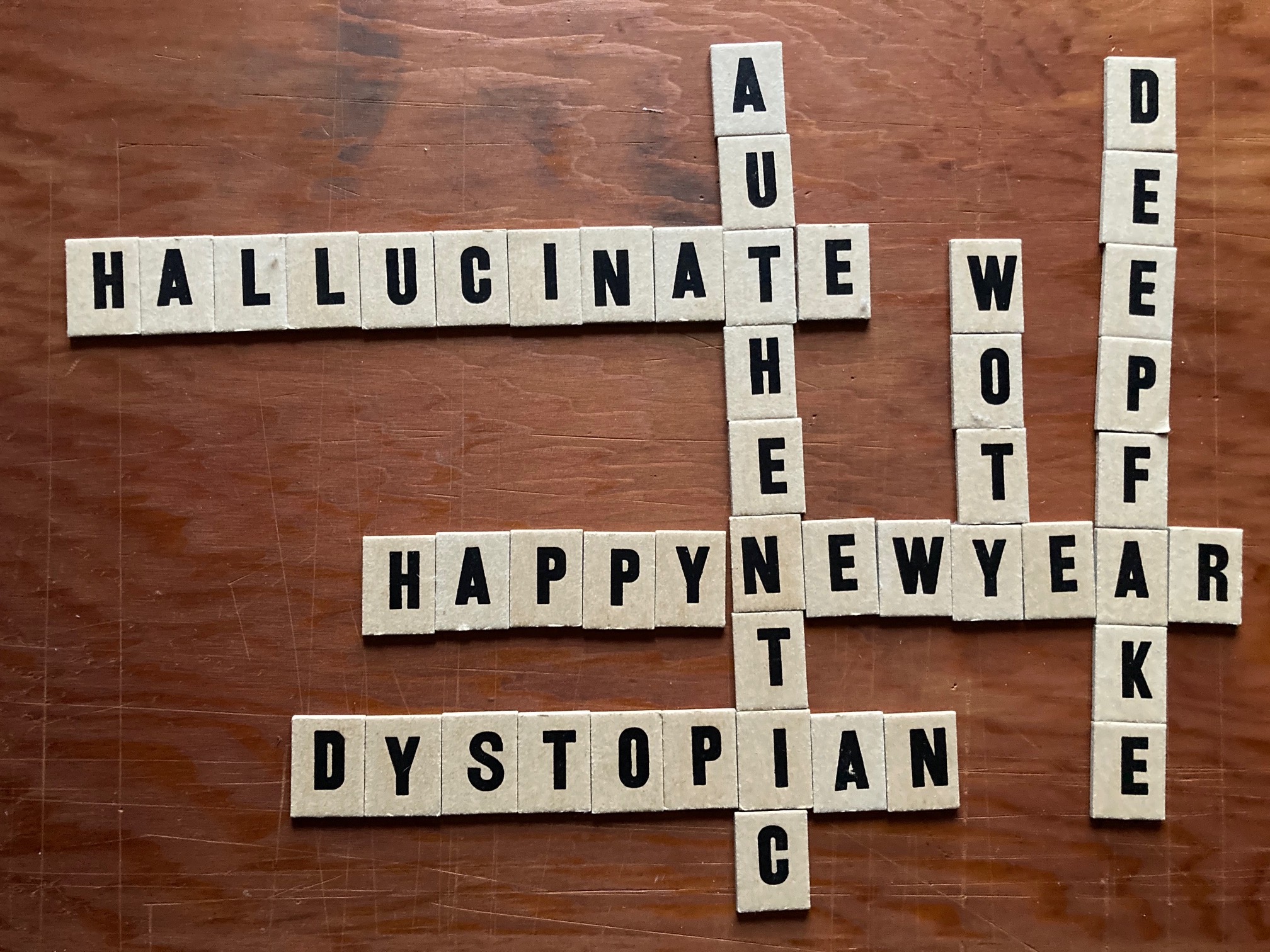

I wondered if alphabetizing by first name was a new trend in indexing. I posted a query on the Indexing Society of Canada email listserv, asking if anyone had been asked to use this format. Three indexers wrote to me with thoughtful comments.

Judy Dunlop, an indexer based in Edmonton, told me about her index for Our Long Struggle for Home: The Ipperwash Story, published by UBC Press. She described the book as “an oral history on the police shooting of Dudley George in 1995” and said that “many individuals were referenced only by first name in the text.” This led to the decision to use a mix of inverted and non-inverted names in the index. The headnote for the index reads: “Names of the Nishnaabeg are alphabetized by first names. Other names are alphabetized by last name, first name. A partial George family tree is on pages xvi-xvii.” The family tree helps readers find different members of the George family by their first name.

Joy Tataryn, who works as a legal editor, sent me a link to the website for Clark Wilson, a Vancouver law firm, which lists its staff by first name. We agreed that this makes sense, as people who work with the lawyers may be more familiar with their first names. Joy also thought it was refreshing—a unique approach.

I realized this was my feeling too. When I first saw the list of names in Incandescence, my reaction was “Well, that’s wrong!” But then I thought, “I’m saying it’s wrong because that’s not how I would do it,” which made me wonder why we invert names in indexes.

Leafing through various indexing texts, I found only one that specifically answered this question. In the second edition of Indexing Books, Nancy C. Mulvany writes, “When personal names are cited in an index, the name is often inverted so that the surname will be the keyword for sorting” (page 86). In her index, “inversion” appears as a subhead under “names, personal.”

The Chicago Manual of Style makes the same argument, though it’s not specifically about names. Section 15.9 says, “The main heading of an index entry is normally a noun or noun phrase—the name of a person, a place, an object, or an abstraction. … A noun phrase is sometimes inverted to allow the keyword—the word a reader is most likely to look under—to appear first.” This is followed by examples, including “Aron, Raymond.” The discussion is indexed under “inversion” but not “personal names.” Clearly, CMOS assumes that indexers will know this convention or will pick it up from the examples.

Noeline Bridge, editor of Indexing Names, a treasure trove of information on, well, indexing names, also replied to my listserv query. “I could imagine circumstances in which an index ordered by first name could be justified: to a book comprising names of people commonly addressed by first name, followed (or not) by patronymics/matronymics or other designation apart from surname—e.g., Russian, Icelandic names, names of people in biographical works in which people are routinely referred to by given name.”

Patronymics also came up in my discussion with Joy, who is of Ukrainian heritage. She sent me a link to a website on Ukrainian naming conventions and wrote: “In Ukrainian language (and other Slavic languages too, I think), there is also the patronymic inserted between the first name and the surname.” Then there are languages where the surname or family name comes first (many Asian languages), where there are compound family names (Portuguese, Spanish), where a single name is used (Indonesian), and so on. There’s a reason Indexing Names is a packed 384 pages!

As with all indexing—and writing and editing—you have to keep in mind how people might be using your index. You also have to know the naming conventions of different cultures. And you have to recognize situations where alphabetizing by first name might make more sense than the traditional format of last name first.

[1] This seems to be a bad example of indexing generally, with entries that are surnames only (Beethoven, Dostoevsky); entries that begin with a title (Archduke Franz Ferdinand); entries that begin with and are alphabetized by Die, the German equivalent of “The,” which is usually inverted (for example, Joy of Cooking, The, rather than The Joy of Cooking); and the bizarre entry “an old pitcher” (if someone were looking for a reference to a pitcher, I imagine they would look under p for “pitcher” or possibly o for “old pitcher,” but not under a!).

Comments (3)

Comments are closed.

Thank you for this! So interesting and a good reminder of the importance of being flexible and curious. I was just wrestling with this as I built a style sheet for a new client–I wanted it to be useful and handy for the proofreader (of course) and spent some time thinking about how I could best alphabetize the word list. Also: Hi, Audrey! 🙂

Thanks, Tanya. I’m glad it’s helpful. I’ve seen a lot of style sheets where they alphabetize by first name—though I’m not always sure that’s the best idea. As with so much of indexing (and editing), it depends.

Good to hear from you!

McClellan, Audrey

Hi there, Audrey! This is really interesting. Lately, when I proofread, I’ve been receiving style sheets alphabetized by first name more frequently. I’d also wondered whether this is a trend that is catching on generally.