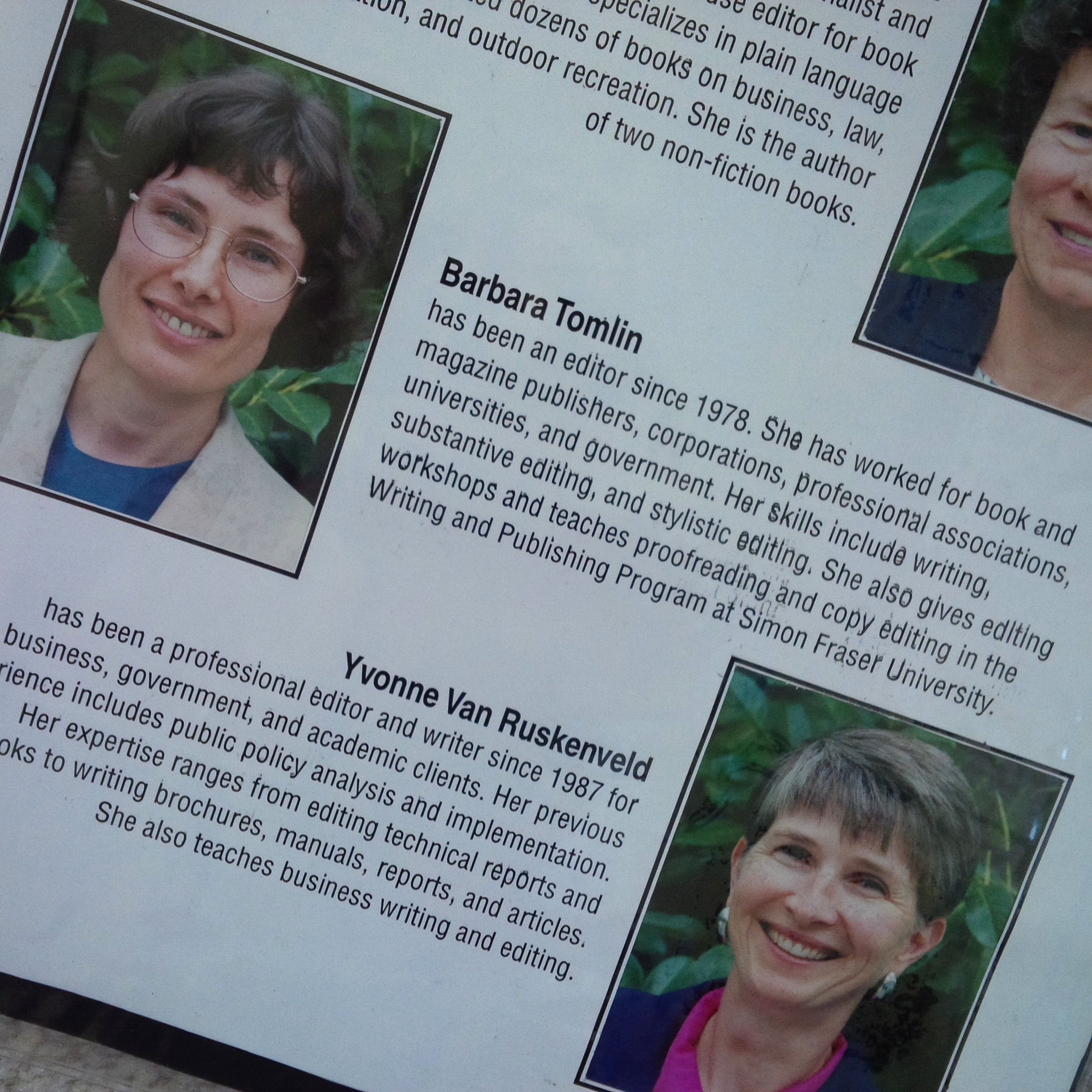

Last month, WCEA partners gathered for a long-overdue celebration of former partner Frances Peck’s retirement.

If we weren’t persons, who were we?

As editors, we know the power of choosing the right words to get a message across to readers. As readers ourselves, we see how words can change people’s perceptions: are the thousands of people on the move “migrants”—or are they “refugees”? When does a “freedom fighter” become a “terrorist”?

As editors, we know the power of choosing the right words to get a message across to readers. As readers ourselves, we see how words can change people’s perceptions: are the thousands of people on the move “migrants”—or are they “refugees”? When does a “freedom fighter” become a “terrorist”?

Since 1992, October has been Women’s History Month in Canada, celebrating an event that arose out of one word: “persons.” International Women’s Day is on March 8—so why is our commemoration of women’s history in October? In that month, in 1929, Canada’s highest court of appeal (at that time, the Privy Council of Great Britain) decided that women belonged in the legal definition of “persons.”

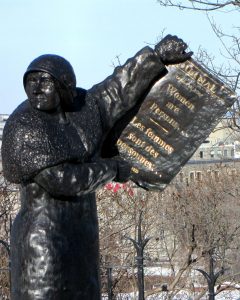

The Privy Council was considering the question of women as persons because the Supreme Court of Canada had decided that women were not persons. The case was sparked by the experiences of Emily Murphy, the first police magistrate in the British Empire. As a magistrate in Edmonton, she faced challenges from lawyers who claimed she had no right to pass sentences because of an 1876 British common law ruling that stated, “women are persons in matters of pains and penalties, but are not persons in matters of rights and privileges.”

Emily Murphy stepped up to these challenges, and along with Henrietta Muir Edwards, Nellie McClung, Louise McKinney, and Irene Parlby—the “Famous Five”—questioned the meaning of “persons” in section 24 of the British North America Act of 1867. Section 24 related to appointment to the Senate: no woman could be appointed to the Senate because the definition of “person” was limited to men. The Senate may no longer be considered the august body it once was, but the case was not just about that. The Famous Five, the government, and the Privy Council recognized that this limit in the definition restricted women’s full participation in public life.

The wording of the Privy Council’s decision still resonates today: “The exclusion of women from all public offices is a relic of days more barbarous than ours. And to those who would ask why the word ‘person’ should include females, the obvious answer is, why should it not?”

So if we weren’t persons before that decision, who were we? Of course, we were mothers, daughters, sisters, wives, and lovers, but we were also businesswomen, receptionists, philanthropists, “salesladies,” nurses, doctors, teachers, farmers—all these and many more. For example, let me introduce you to some of the women I’ve talked about on my annual Women’s History Tour in Ross Bay Cemetery here in Victoria over the past 20-plus years (October 4 this year):

- Isabella Ross (1808–1885): first woman and first Aboriginal person to be a registered land owner in British Columbia

- Agnes Deans Cameron (1863–1912): teacher, writer, lecturer, adventurer

- Maria Grant (1854–1937): social reformer and suffragist

- Nellie Cashman (c. 1845–1925): prospector, miner, businesswoman, philanthropist

- Gladys Wake and Christina Campbell: World War I Nursing Sisters—they may not have been “persons” in the eyes of the law but they died while on duty for their country

This year’s theme for Women’s History Month is “Her Story, Our Story: Celebrating Canadian Women.” What are the stories of women who came before you in your family? What were they doing before—and after—they officially became persons? We are each our own persons, but we are also those who came before. Celebrate!

Postscript:

Postscript:

The Persons Case had ramifications far beyond women’s rights. The Privy Council, in its decision, changed the view of our constitution from being a fossilized entity to “a living tree capable of growth and expansion within its natural limits,” able to change organically with our society. The concept also lives on in our Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which Chief Justice Antonio Lamer described in 1985 as “the newly planted ‘living tree.’”